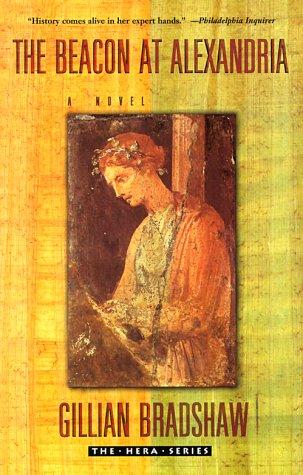

Gillian Bradshaw has written more accomplished books than The Beacon at Alexandria, but none that I love more. It’s a comfort book for me, fitting into a sweet spot where she does everything just the way I like it. It’s set in a period I’m especially fond of (the period leading up to 376) she gets all the details right but never makes you feel you’re suffering for her research, the protagonist is a woman who disguises herself as a man (well, a eunuch, which is even more interesting) and is just the right kind of unsure and then confident. I even like the romance. But best of all it’s about my favourite subject, civilization and why it’s a good idea. I relax into this book as into a warm bath.

Charis is a young lady of good family in the city of Ephesus. She wants to be a doctor, she reads Hippocrates and practices on sick animals. To avoid a horrible marriage she runs away to Alexandria and studies medicine in disguise. There she becomes entangled with the Archbishop Athanasius. She leaves Alexandria in the disturbances after Athanasius’s death to become an army doctor in Thrace, up on the frontier, and there she becomes entangled with some Goths. The historical events are a tragedy, in the sense that they inevitably go along their course towards no good end. The personal events are not. We have here the story of one person going through her life and learning and loving, against a background of everything going to hell.

Oh, and it’s arguably fantasy. There’s an oracle that comes true, though it’s entirely historical that it did, there’s a divine vision that Archbishop Athanasius has, and a dream-visitation from him after his death. That’s not much, and it has always been published as a straight historical novel, but you can make a case for fantasy if you want to.

It’s an intensely feminist novel. The contrast between what Charis can be as a woman and be as a man is one of the main themes of the work. She lives in fear of exposure and in hope of one day being able to live as what she is, a female doctor. Yet she knows that without the spur of needing to escape she would have kept on compromising and never living her own life. She sees all her options as a woman—marriage to an appropriate stranger—as a cage. We later see a little of it from the male side. The men complain that nicely brought up girls look at their feet and have no conversation—which is precisely what Charis is being trained to do. Even marrying her true love who is going to let her run a hospital, she has a pang over that “let” and needing to trust him so much. I often find feminist heroines in historical periods revoltingly anachronistic, but I don’t have that problem with Charis at all, because we see the process of her growing into it and her disguise becoming second nature. The disguise as a eunuch is interesting too. It makes her asexual. Rather than switching her gender it takes her out of gender altogether. You’d think people would write more about eunuchs, in the periods where they existed. Mary Renault’s brilliant The Persian Boy has a eunuch protagonist, but apart from that I can’t think of much about them. The disguise gives Charis a position on not being able to marry, and it means the disguise doesn’t need to be as entire as it would otherwise be—eunuchs are supposed to be girlish men, she’s a girl in man’s clothes. Women have in reality passed as men, sometimes for many years; James Barry lived as a doctor for decades. It’s nevertheless always a difficult thing to make plausible in fiction.

The period details of medicine are convincing, and Charis’s passion for medicine is very well done. She is just the right degree of obsessed with it. I have wondered if Charis inspired the doctor Jehane in The Lions of Al Rassan or whether it was more recent struggles for women to become doctors that inspired both of them.

This is a book set at a time when the Roman Empire had been in existence for centuries and from within and without it looked as essential and unnoticeable as oxygen. The battle of Adrianople which comes at the end of the novel marks the beginning of the end of that Empire, in the West. The characters of course do not know this, but Bradshaw is achingly aware of it, as almost any reader must be. I don’t know how the naive reader who’s learning history randomly from fiction would find it, I was never that reader for this book. I always read it with the full awareness of the historical context. Bradshaw makes the period very real, the ways in which it is similar to the present and the ways in which it is vastly different. She doesn’t make it nicer than it was, the corruption and bribery of the officials, the horrible position of women, the casual acceptance of slavery, and torture of slaves for information. Yet:

One takes things for granted, assuming that something is a natural state when really it is a hard won privilege. It had never seemed odd to me that only soldiers bore weapons, that the laws were the same everywhere, that people could live by their professions, independently of any local lord, that one could buy goods from places thousands of miles away. But all of that was dependent on the Empire, which supports the structure of the world as Atlas was said to support the sky. All of it was alien to the Goths. I had hated the imperial authorities at times, for their corruption, their brutality, their greedy claim on all power in the world. But now that there was a challenge to the imperial government of Thrace, I found myself wholly a Roman.

This despite the Goths allowing women doctors. Bradshaw is quite fair to the Goths—giving them the virtues of their flaws, culturally, and individually. But it’s the corrupt civilization of the Empire that she loves, and that I love too. Most of Bradshaw’s work has been set there—the Arthurian books and Island of Ghosts in Britain, Cleopatra’s Heir in Egypt, Render Unto Caesar in Rome, The Sand Reckoner in Sicily. She writes about it from inside and outside, in many different periods, from its beginnings to its endings, but almost always the Roman Empire, flawed, imperfect, but representing peace and civilization. The “beacon” at Alexandria is the lighthouse, but it’s also the library, learning, the shining possibility of education.

If you ever feel homesick for the Late Roman Empire, or if you’ve never been there and want to visit, you can do a lot worse of this story of a girl disguised as a eunuch becoming a doctor and having adventures.